With the pandemic shifting how so many workplaces function, facilities managers have seen a growing list of responsibilities in the past three years. In addition to rethinking real estate and office space design to accommodate changing work models, integrating more data into operations and adapting to evolving guidelines around sustainability, facility managers are also being forced to run with stricter budgets, comply with new building regulations and still ensure smooth day-to-day operations.

Some of the role has stayed the same since before the pandemic. They still have to hire and organize personnel, manage contracts, keep up with preventative and emergency maintenance, handle inventory, negotiate leases and fill empty space in their buildings.

But a number of ongoing factors has caused each of these tasks to grow more complex, time-consuming and costly. So where are facility managers focusing their attention? Below are some of the major trends affecting the facilities management industry in the second half of the year.

Buildings are getting more complex

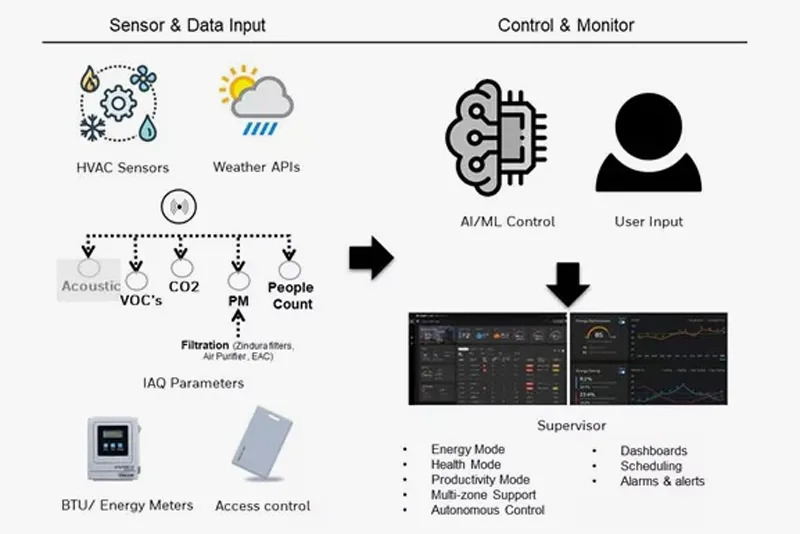

As technology advances in and outside of buildings, facility managers are increasingly tasked with managing new systems. Core HVAC, electrical, engineering and safety systems are all being upgraded to be more energy efficient, more interconnected and increasingly integrated with IoT systems via building information systems, which monitor functions and report data to operations management platforms.

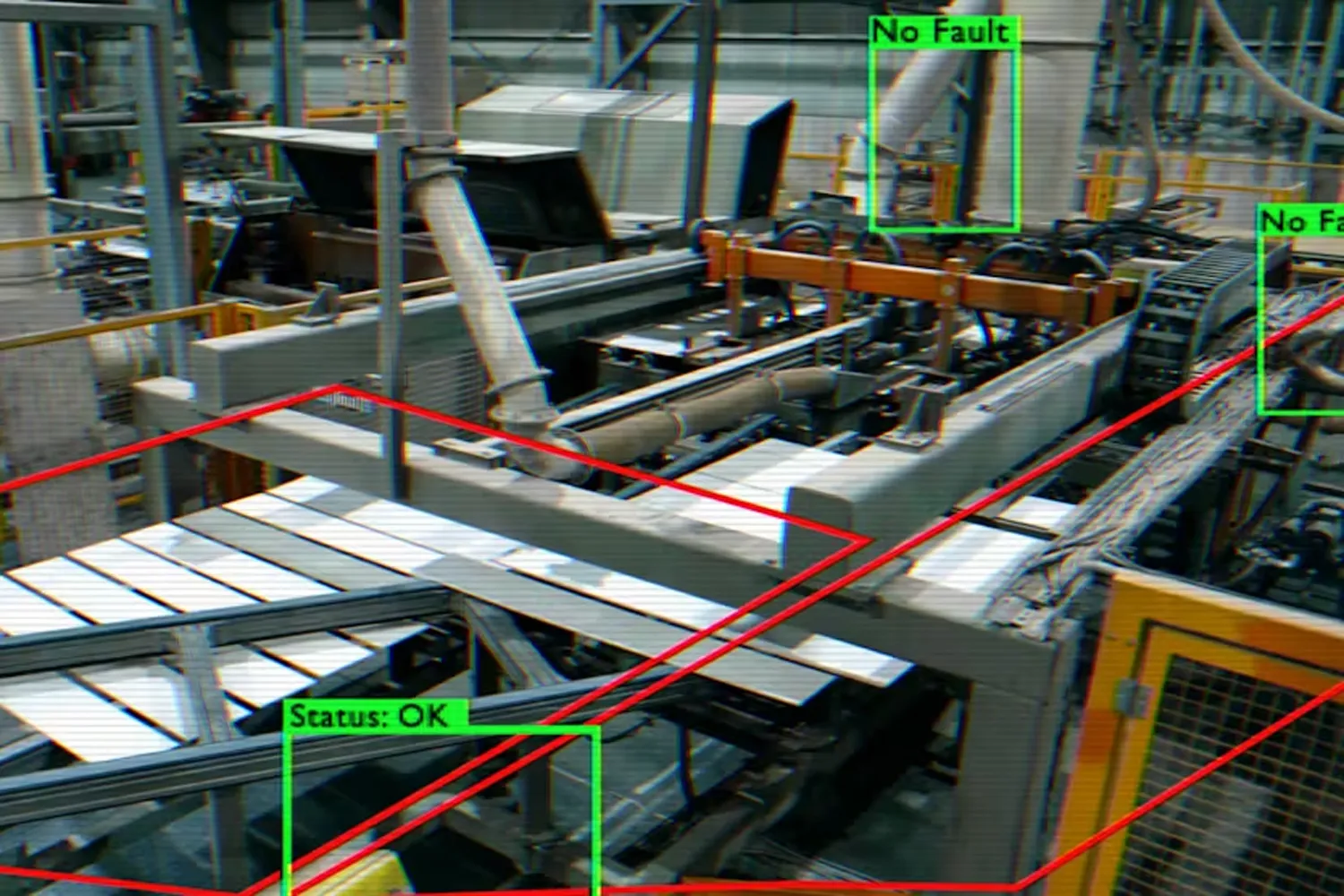

Buildings, for example, are getting updated air filtration systems, originally spurred by pandemic concerns. There are also new electrical management systems that control the flow of electricity to essential infrastructure and AI-driven sensors that detect unusual behavior and alert security officials.

By taking a more unified approach to building management, oftentimes through integrated workplace management systems, facilities managers can gather information from both amenities and operations segments to better understand a facility’s strengths and weaknesses, as well as introduce workflow efficiencies.

But with new upgrades comes new needs for wireless and wired internet, cybersecurity and IT systems. All require expertise to operate and could bring a building to halt if they fail, leading to an immediate loss of revenue and expense to fix.

While facility managers have traditionally come from technical backgrounds, with many previously working as hard skill technicians, these new systems require even more complex knowledge about a facility's operations and ability to understand the data coming in from all the various technologies. A recent survey by Toggled found that while a majority (78%) of facility decision-makers have deployed smart building features, over a third (38%) say they lack the skills and talent to integrate the required data science into their smart building platforms.

“There are so many different sources of data now. It used to just be sort of, ‘I've gotten my utility bills from my electric and gas company, maybe we're using a little bit of diesel in our generator, something like that,’” said Dan Scher, vice president of strategic planning and environmental stewardship at Medxcel. “Now, as you get into more of a carbon oriented world, those data sources sort of explode exponentially. And so you're getting into a lot of other parts of the business that may not have been just traditional facilities focus.”

As the number of data sources continues to grow, facilities managers must learn to gather, organize and analyze this information in an efficient way.

In addition to electrical, mechanical, plumbing, lighting and structural maintenance data from traditional facility condition assessments, management is now tracking a litany of other data types and sources. These include climate sensors, occupancy and office scheduling, air filtration, carbon emissions, safety system inputs and third-party work order information, among others.

“The No. 1 challenge is data, and getting good clean data that you can analyze,” Scher said. “I think most facilities managers have a good working sense of the facility and being able to couple that experiential learning with the data, I think, is a differentiator.”

As a result of this technical growth, companies like Infogrid, BrainBox AI and Sidewalk Labs are popping up to connect all of a building’s data in new ways, using this information with AI to determine efficiencies and automate building controls. While these next-generation buildings may not be the norm for a while, if ever, they point to a future with progressively complex systems that facilities managers will need to contend with.

More building regulations push facility managers to adapt quickly

On top of the complexity, buildings are being regulated more at federal, state and local levels, such as California’s AB 2446, which requires life cycle assessments and environmental product declarations in new buildings, and proposed AB 593, which would require the California Energy Commission to craft a building emissions reduction strategy with milestones to be implemented by 2025. There’s also New York City’s Local Law 87, which requires energy audits and retrofitting for buildings within the city.

Evolving environmental standards around the country have pushed many organizations and municipalities to focus on improving their buildings to operate more sustainably to lower their carbon emissions.

The 2023 National Electrical Code was also published at the end of last year, ushering in new codes and standards for building operators. Many of the updates since 2020 focus on the importance of technology in today’s buildings, with the new code granting electrical authorities the ability to examine cybersecurity considerations and encouraging enhanced energy efficiency through the use of energy management systems and electric vehicles.

“Benchmarking is absolutely that first step that you need in order to initiate further actions, like a building performance standard, because you very much need all of that data.”

Ben Levine

Program manager, Buildee

Air quality is another building component pushing facility managers to adapt, with multiple government agencies and industry regulators beginning to create standards and guidelines for ensuring safe air in buildings.

Most recently, the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers released a draft for public review of its first-ever standard for mitigating the airborne spread of infectious pathogens in indoor spaces. The announcement came soon after the CDC offered guidance on building ventilation, recommending at least five air changes per hour of clean air in occupied spaces.

Benchmarking gains significance amid all the data

Shifting regulations creates a glaring issue: Many facility management companies don’t know how their buildings stack against these goals. This leads facility managers to question how they can improve to meet regulations in an economically feasible way.

Another problem is that while there are standards and building codes that ensure safety, many facilities management-oriented benchmarking often lacks a strategic position in organizations and is often performed by individuals with no formal benchmarking experience, leading to underperformance in evaluating buildings and creating action plans, according to a research paper from UNC-Charlotte.

Sustainability benchmarks related to carbon output, net-zero offset credits and emission scopes are still being ironed out and differ between municipalities and regions, creating confusion.

“Benchmarking is absolutely that first step that you need in order to initiate further actions, like a building performance standard, because you very much need all of that data,” said Ben Levine, program manager at Buildee, a software provider for municipalities, utilities and building owners.

“It's sort of like crawl before you run. You would not be able to put forward a building performance standard if you hadn't already put forward a benchmarking policy over a few years, which enables you to gather all of that data, understand exactly what sort of structure your building performance policy should take, what sort of timeline it should have, what owners should be tackling first,” Levine said.

Organizations that implement regular facility benchmarking programs experience improvements and savings in their operations, but this requires support from top management all the way to the professionals running operations on the ground floor.

Rise in amenities, hospitality services to make properties more attractive

The shift to remote, hybrid and flexible work models has slashed the amount of office space needed by companies, and put pressure on building owners to offer new amenities and services to attract tenants. So in addition to running critical infrastructure of a building, facilities managers are also often tasked with sourcing and overseeing amenities, such as health and wellness centers, transportation hubs, daily convenience markets and more.

SGA’s recent Workplace Amenities Report reflects these larger societal shifts, with survey respondents demonstrating a greater focus on personal well-being and safety, interest in sustainable modes of transportation, convenient places to grab food and packages, and spaces that facilitate social interaction.

According to the study, 45% of respondents said a “post-workout nourishment station” is a must-have or strongly desirable, while 67% had the same sentiment about having a basic unstaffed fitness center. Almost half (49%) said a convenience store was at least highly desirable, and 75% said a grab-and-go providing pre-made breakfast or lunch was desired.

Almost half of respondents also said bike parking was strongly or somewhat desirable, which in turn also leads to greater security needs for facility managers.

Labor issues will continue to eat into operating costs

Labor is one of, if not the largest, expenditure for facility managers currently, according to the 2022 Facilities Management Cost Trends report by CBRE, with it unlikely to decrease even after workforce shortages and logistics challenges resolve.

While supply chain challenges have softened since then, the labor market hasn’t, with organizations and operators of all scopes and sizes experiencing difficulty in sourcing and retaining labor. This has led to continuing wage increases and high employee churn, in turn creating high training costs and making it hard for facility managers to maintain their staffing levels.

Another field service operations report by Blumberg Advisory Group echoed these sentiments among operators, finding that labor supply of W2 and 1099 employees was the most significant factor for rising operating costs (25%), followed by higher prices for spare parts and tools (23%). It also found that the inflated costs of these two segments were the most common challenge that operators face in achieving high customer satisfaction (48%).

Outsourcing and out-tasking has proven to be an effective way for many building owners and facility managers to alleviate some of the pain associated with the current labor market. However, it takes control out of an organization’s hands, leading some to question if it is a reliable way to cut costs.

“Trends would dictate that when times are bad, companies tend to outsource more,” said Mia Mends, chief executive of Cushman & Wakefield’s facility services subsidiary, C&W Services. “What I’m seeing is our current clients are looking for discounts, and I’d say first-generation [clients are] also wary, because it’s an unknown. There’s an aversion to risk.”

Despite what Mends says is a 50-50 split between in-house and outsourced facilities service, she believes that ongoing economic pressures do have the potential to further increase the amount of organizations that choose to outsource their facilities' labor.

“But I think we’re slowly seeing more first-generation clients. Ask me in a year, I want to get through this year, potentially a recession and we’ll be able to answer that question, but technically there should be a positive correlation between economic decline and more outsourcing. I’ll tell you next year whether or not we were able to prove that,” Mends said.

New skills are needed as job duties expand

Since facilities management professionals traditionally come trained with hard skills like electrical or plumbing, they are used to handling maintenance — from repairing water heaters to replacing air filters — themselves, but they are now being asked to do more with less. It is becoming much harder to juggle all of these tasks as their jobs also require new skills such as overseeing tech vendors, hiring third-party tradespeople for in-building maintenance or working with IoT professionals to track and maintain building systems.

The expansion of job duties has led to increased outsourcing for a range of functions, including using vendors to offer amenities to tenants, contracting with a third-party company to handle landscaping or waste removal, or shifting all hard facilities maintenance to a large servicing firm.

A recent CBRE report, “Facilities Management Procurement Perspectives,” found that 58% of organizations' primary facilities management model is outsourced, with another 25% saying they primarily out-task (using third-parties for tactical roles like janitorial or engineering). Only 15% of respondents said the majority of facilities management staff is in-house, highlighting market growth for facility management service providers like CBRE and Cushman & Wakefield, and the rising need for those in-house facility managers to find external labor for specific tasks.

This growth of outsourcing is placing a greater importance on skills like communications and negotiations. There is also a growing pressure for facilities managers to report to stakeholders.

The CBRE report, which sampled facility managers’ procurement and corporate priorities, found that business leaders are paying closer attention to real estate portfolios due to its potential for achieving sustainability goals, driving cost savings and fostering company culture.

The survey, which included responses from more than 40 corporations in varying sectors, found that 20% of facility manager procurement leaders called employee and stakeholder satisfaction as their “top priority,” second only to quality and service improvement (23%) and ahead of competitive pricing and cost savings (19%).

Predictive data could create shift from reactive to proactive model

At the core, a facilities manager is tasked with keeping buildings running smoothly, generating operational efficiencies and making sure tenants are happy. The growing adoption of sensors and new data sources provides more things for operators to keep track of, but also a lot of information to inform building decisions and create labor efficiencies.

A key example would be for maintenance. According to a webinar with JLL Technologies, which discussed its soon-to-be-released State of Facilities Management survey, managing routine tasks and maintenance take up the majority of time for more than half of respondents. The report states this is where facilities managers are most reliant on automation, due to increased workloads and staffing issues.

In turn the survey also found that most facilities managers (67%) see building a predictive maintenance strategy as their top asset management priority in the new year, with JLLT also noting that 41% of all assets tracked on its Corrigo computerized maintenance management system software are on preventative maintenance schedules.

The adoption of integrated building management technology means managers can have greater insight and control into the systems that keep a facility running and can use this information to generate action plans, create maintenance schedules and demonstrate cost-savings to investors or owners.

Add in occupancy data, gathered from mobile apps or sensors that track employee activity, and operators can begin to have a better view of how specific areas of a facility are used. If a facility manager knows that a certain conference room is used more, they can adjust cleaning and air filter maintenance schedules to account for that. If they know that a storage area is only used a few times a year and doesn’t have much traffic, they can keep the temperature colder and replace the lighting less frequently.

All of this enables operators to shift from a reactive approach to a proactive maintenance model, which protects facility budgets from expensive emergency repairs and outages. This also means that facility managers don’t have to send out technicians as often to repair or maintain less-utilized equipment, enabling them to focus their resources on more important jobs.

While industry adoption for these integrated, predictive building systems is still ramping up, it appears this technology will be a crucial factor for operators moving forward.

“The next level is having more modern building management systems, having automation around it and having the ability to auto schedule certain capabilities in the building that way,” said Sadiq Syed, vice president and general manager of Connected Enterprise at Honeywell.