Dive Brief:

- Building performance standards are gaining regulatory ground as a way to decarbonize buildings, market consultations and commercial real estate professionals said during a panel at an ASHRAE conference on Oct. 25.

- The panel focused on how Washington, D.C.’s Building Energy Performance Standards, now two-and-a-half years into its first cycle, are changing the existing building market and policy-related challenges and opportunities.

- D.C.’s building size threshold will drop for the second cycle, starting in 2027. It will require private buildings over 10,000 square feet to begin reporting energy performance data, affecting over 5,000 buildings in the district, with more than half needing to improve energy performance before then.

Dive Insight:

There are currently 45 jurisdictions that have signed on to the President’s National BPS Coalition, which means they have committed to adopting building performance standards legislation by Earth Day, or April 22, 2024, according to Mary Thomas, associate director at the Building Innovation Hub at the Institute for Market Transformation, who led the panel.

Washington, D.C. is one of the first jurisdictions to implement BPS frameworks, requiring buildings over 50,000 square feet to be benchmarked since 2013, prior to the start of its first BEPS cycle in 2021. It officially set standards in 2021, when buildings over 25,000 square feet began benchmarking their energy performance. The standard for each property type is the median energy performance in the jurisdiction for all buildings of that property type, Thomas said, meaning that if a building is performing better than the median for its type of property, it is not required to take action under that cycle. She noted that the first major deadline in Washington happened on April 3, requiring buildings to select a pathway to reach performance standards.

Cycle two begins at the start of 2027 and coincides with the BEPS compliance deadline. After then, buildings over 25,000 square feet will have to report benchmarking data to prove compliance.

“That means that any retrofit measures will need to be completed by the end of 2025, to have a full year of benchmarking data by the end of the compliance cycle,” Thomas said. She noted the district will also reevaluate aggregated building performance, meaning that it will likely raise the level of performance for the next BEPS cycle in order to meet climate goals. “This is why even if your client's building is performing well now, you have to maintain or improve performance over time to ensure it will be performing better for the next standards that are released,” Thomas said.

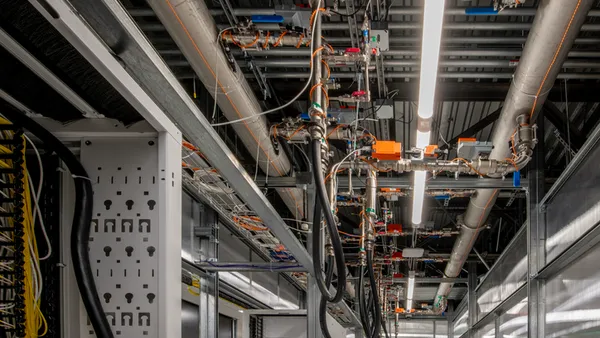

The panel also noted that the possible penalty for non-compliance is up to $10 per square foot, or up to $7.5 million in total. The panel highlighted current challenges facing compliance, including the capabilities of on-site operations and maintenance staff, the degree of modifications needed to heating and cooling systems and questions related to peak heating and cooling loads.

Accurate benchmarking is critical and the importance of energy audits has increased, with expectations being higher than in the past, panelists said. Speakers also noted that fossil fuel removal and building electrification are near-term considerations, and they recommended including engineers in client decision-making to match a compressed timeline for energy performance improvements.

Thomas also pointed to a recent technical guide, developed and released by The American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers in May, aimed at addressing the challenge of decarbonizing the building stock. She said the guide provides in-depth background information on building performance standards to assist policymakers and practitioners in “developing a BPS policy that advances decarbonization and energy efficiency in existing buildings.”