Facilities managers can help their organizations avoid lost productivity from super-spreader events by installing ceiling-mounted ultraviolet bulbs whose short wavelength makes them safe even when people are present, says the head of a technology company that manufactures the bulbs.

Ultraviolet C light at 254 nanometers is the standard for eliminating airborne and surface pathogens from bacteria, viruses and mold, according to the National Center for Biological Information. But its efficacy has been limited because the skin and eye damage it causes means that it can only be used when rooms are unoccupied, John Rajchert, CEO and co-founder of UVC company Lit Thinking, told Facilities Dive.

The groundwork for changing that was laid several years ago when researchers discovered so-called far-UVC light – ultraviolet light at 222 nanometers – that can provide the same germ-killing efficacy without the health risk.

“That wavelength does not penetrate human skin or eyes,” Rajchert said. “That means we can have it continuously operating even when the room is occupied, which is a huge benefit in terms of reducing viral load.”

Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City and Lake Erie College of Osteopathic Medicine in Pennsylvania are two healthcare facilities that have installed the company’s far-UVC bulbs in early case studies to test how well the bulbs work. Roger Williams University in Rhode Island is also using the bulbs in a test case. UL has certified the bulbs as safe.

“Everyone knows ultraviolet light is great for killing germs but [it’s also recognized] you can’t be present in the room,” Rajchert said.

To help ensure the safety of the bulbs, his company says it adds filters to prevent them emitting any wavelength over 230 nanometers.

“It’s a matter of market adoption,” he said. “We want to keep demonstrating in a number of use cases that, not only is it safe, but it’s a practical way of solving the problem of how you create a safer building environment for occupants.”

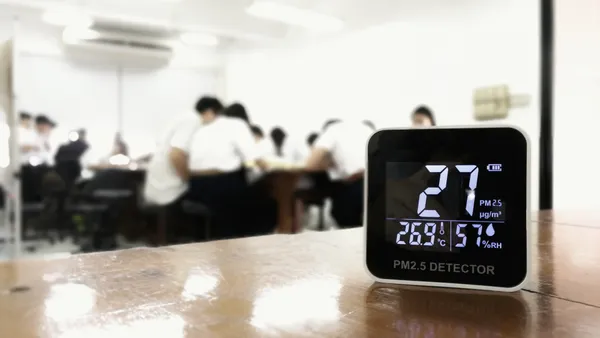

Rajchert sees the bulbs as a way for facilities managers to remove pathogens and improve indoor air quality without having to sacrifice energy efficiency by using the bulbs to generate the equivalent of 30 air changes an hour.

“By bringing a regular room up to 30 air changes per hour with a small number of devices, [within] 12 seconds you would be dropping 50% of pathogens out of the air from a baseline,” he said. “Within 30 seconds you would drop 90% pathogens and within a few hours, 99.9%.”

Each bulb covers about 200 square feet and mounts in a fixture that’s designed to be installed flush with the ceiling.

“It requires a 6-inch cut out,” Rajchert said. “It does have some size to it, but no more than a typical light fixture.”

Bulb life is 10,000 hours, or about two years of continuous use, he said.

“It’s as simple as putting in a three-wire, 110 to 277 volt light fixture,” Rajchert said. “A standard electrician could do it.”

So far, medical facilities, which lose about 100,000 people a year in the United States to infections that patients acquire on site, have the most interest in the technology, he said. But any facility in which there’s a steady interchange of people could find it a cost effective way to cut the spread of pathogens, he added.

“People are never sure where they pick [an illness] up,” he said. “Was it in the elevator or in the supermarket? What this does is prevent a super-spreader event at work. Someone comes into work sick, infects a dozen other people.That’s a real issue. So, it’s about preventing that.”

Rajchert’s company is hoping to work with up to 50 organizations on case studies, similar to what it’s doing with Mount Sinai and the other early adopters, to build a body of evidence on the technology’s efficacy and safety. Lit Thinking would install the bulbs in one or two rooms, take before and after swabs to measure change in pathogen levels and then compile the results in published co-branded case studies.

For participants that find the results positive, they can work with the company to fill out the rest of their space with the bulbs.

In return, Rajchert’s company gets data. “We want to build out that database,” he said.