Fifteen years ago, building lighting was fairly straightforward. A facility manager would install the lights and replace them as needed when they burned out. It was a different era when Altair Engineering saw large-scale improvements in LED and launched its subsidiary Toggled in 2007 to provide energy-efficient lighting to businesses across the globe.

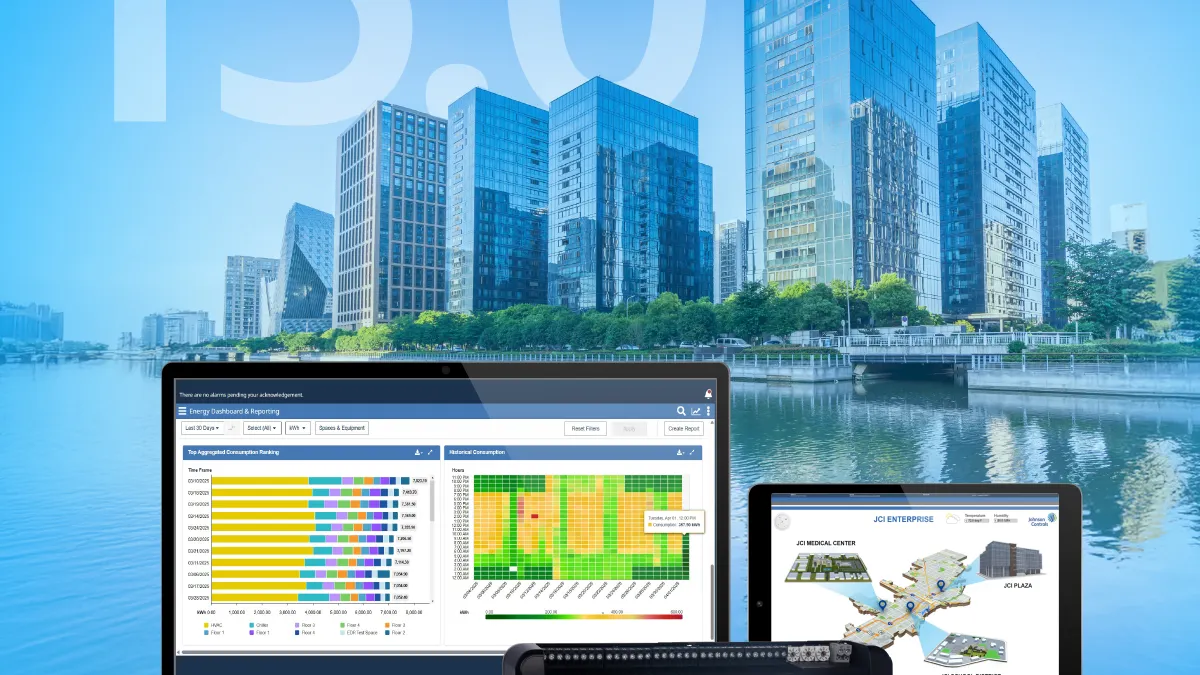

Times have changed, and building operators are demanding more from the systems. They require technology that connects lighting, heating and edge sensor-led data sources to maximize cost efficiencies. To meet this demand, Toggled has evolved from a lighting supplier to an integrated systems hardware and software provider, with the company recently launching its Toggled iQ product to offer an IoT-enabled building analytics and control platform.

Facilities Dive spoke with Dan Hollenkamp Jr., chief operating officer at Toggled, to discuss the growth of integrated facilities systems, challenges that facilities management faces in adopting this technology and how efficient systems can drive cost and carbon emission savings.

Editor’s note: This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

INDUSTRY DIVE: What are the biggest challenges with aggregating, analyzing and using all of the data from buildings?

DAN HOLLENKAMP JR: Honestly, the biggest challenge with data is collecting it and getting it somewhere that it can all be aggregated together, especially when you have buildings with multiple technologies and multiple protocols.

You'll see lots of charting in financials and in other industries, but buildings don't have as many tools available. It's really important because we don't know how buildings are operating. What permanent buildings use the most energy? Is part of my building being cooled more than another? It's hard to tell. We're really flying blind.

Traditionally, most things have been set on schedules. The setback changes at this time, temperature changes to this at this time, and it's set it and forget it, right? Unfortunately, the way we use buildings is changing. Within the last few years ... these common use patterns are gone. Even if there's someone in the building every day, we're not using the same part of the building every day, and it changes very fast. It could be tomorrow, all of a sudden we're not coming in, and we don't have the luxury of everyone in this normal 9 to 5 workday anymore. So it is even more important to understand where we're wasting energy and how buildings are operating.

Do you see more standardization of technologies as new sustainability mandates are implemented?

When it comes to standardization, it's really difficult because you don't want to standardize on something that's limiting. Let's say we all standardize on this specific protocol, and two years later we found something that's way better. Do we adopt the new technology that's better or do we keep the old technology because that's what we standardized on? There's a lot of challenges with standardization and optimization. The way we solve it is by having a platform that supports multiple protocols.

All of our products can be upgraded in the field. All the time we have requests for different features. We can develop it and roll out a firmware update, and all of the existing devices in the field now have that functionality. I think that more important than standardization of protocols is to make sure that there's always a path forward — so being able to upgrade to adapt to new energy standards.

We don't know [if] there could be a completely new requirement next week. Now we're going to use a different control strategy for lighting. Maybe all of a sudden demand response becomes a big thing, right? We haven't seen demand for responsive lighting become that isn’t popular yet. Mostly, it's HVAC. But because our system can upgrade, and we can change its behavior years into the future, it future proofs you so you can be confident that your investment will actually pay back.

Your recent survey talked about how users are seeing energy efficiency improvements and cost savings but not much measurable decarbonization. How that can improve?

Decarbonization is complicated. There's only so many things you can do, and we still have to buy devices to put in — and that's potentially a carbon footprint. A lot of times we don't have control over the energy that we use. As a facility operator, I can add solar, which helps with buying products and devices. I can conserve and reduce the amount of energy that I'm using, but to really decarbonize it needs to be everyone working together. If your power source, which you may not have any control over, is still producing a substantial amount of carbon, there's nothing you can really do about that.

Working together with all players in the space is really going to help. For example, providing demand response to utilities so that they can curb demand helps them deal with a situation where they may not have enough power. It helps them prioritize because, unfortunately, renewables are a little more unpredictable on their output. On the generation side, we're having buildings that are smart connected and can be a part of the utilities control and part of how the utilities are continuing to decarbonize on their side.

If we can aggregate more data for buildings throughout a region, that would help utilities understand what loads are there and what they can expect in the future. The more data that's available, even at a larger scale and looking at regional data, things like that definitely help utilities understand how energy is being consumed. They see the energy going out into buildings, but once it hits the building, [they] are not really sure how it's being used. Knowing how it's used would help them plan their infrastructure better.

The survey found that many building tenants don’t have smart technology and are looking for these things in new leases. You’ve got to retrofit these smaller, older buildings, which is expensive. Are there enough green places for these businesses to go?

I'm seeing lots of conversations about it. There's more and more scrutiny for companies to show their carbon footprint, and it doesn't matter if you own it or rent, it's still your footprint. I think for the building owners who are leasing their buildings to tenants, if they aren't making strides to reduce the carbon footprint of the building, they're gonna have a harder and harder time renting out their buildings. All the buildings that have better footprints are going to get leased first, and probably at a better rate, because for the companies that are leasing them, when they have to do the reporting, it's easier for them.

It's necessary now, especially for public companies, and it’s not an excuse to say ‘I don't own this building.’ I think that is going to help push buildings that aren't owned by the tenant or the operator to improve. So there's a lot of pressure coming.

If you’re running a large facility, you can turn off 100 building lights at one time and that’s going to save a lot. How much actual operational cost savings is there for smaller facilities which adopt this technology in the near term?

There's a lot of savings. Just lighting controls, in general, you can save anywhere from 20% to 80% of the energy you're using. The hard part is that every building is different. Even if you build two identical buildings, they're not in the same spot. They have different heat loads, they have different wind. None of them are the same. It's really hard to just have a blanket control solution for everything and not have it tailored. I mean you could do it, but you are probably leaving energy savings on the table.

Honestly, just looking visually, looking at the data and a floor plan provides a ton of insights. It’s eye opening immediately. You can see this part of the building is standing out. Why is it different than the rest? And you can really start to dig in to see what's going on. There's a lot of opportunity to save energy that you maybe didn't even know you were wasting.

We've seen people who haven't even implemented any kind of cost savings on their HVAC yet. They're just using standard scheduling. But they realized that the schedule was backwards, just looking at the temperature data over time, and you can see that the set points are wrong. But no one's in the building at the time, so they don't know, right? That's where, even for the small buildings, just being able to see what's happening makes a huge difference to verifying that what we're doing is actually making sense.

From lighting to analytics and interconnected building systems, smart tech is clearly opening a whole can of worms. What do you want to do next, and what advancements do you see down the road that excite you?

We now have these connected products. We can control them and get data out. The next step, honestly, is more machine learning and AI. Originally, when I was younger, I used to do live reinforcement for concerts and things like that in college. The test for whether or not you did a good job was if anyone noticed the sound system. If someone noticed it and commented on it, you failed. No one should notice it. They should really notice the performance happening, right?

I like to think of this the same for lighting. If someone walks into a space and they have to adjust the lights, they notice the lights or are annoyed by the lights, we failed. We need to start having systems that through machine learning or AI — whatever you want to call that technology this week — it’s learning what is best. So when I walk in the room, every time at three o'clock for a specific meeting, and I turn on the lights and have to adjust it, I don't have to do that more than a few times. Now the system knows this is the appropriate state for this room, this is the temperature we want, this is the lighting we want. I should be able to do my work, enjoy the space and not think about what I need to change. A building is here to support what we're doing, we're not here to support the building.

How has this technology, and overall building sentiments, changed post-pandemic?

If there's a benefit that came out of the pandemic, I think it's just this revaluation of buildings. We care about the indoor space a lot more now. Not even just lighting. We care more about ventilation, we care about air quality, we care about using energy because we were presented with all these problems.

The knee-jerk reaction during the pandemic was, let's do 100% ventilation. We are going to open the outside air dampers all the way, and we are going to exchange 100% air. It was eye opening, like wow, we're using a substantial amount of energy now because we are cooling all of the air or heating all of the air. I think there's a lot more focus on what's the right balance. We used to just have fixed air exchanges, and that's not the right solution. If there's no one in the building, why are we exchanging air? I think it opened a lot of people's eyes into what's in the air in buildings. The lights in buildings, when are they on and when are they off? I think just trying to optimize how buildings operate.

I laugh that it's easy to make the most efficient building in the world — you just turn everything off. It's easy, at least zero energy, but it's a terrible place to be. No one wants to be there. It's uncomfortable. It's bad for your health. So it's finding the balance.

And we’re coming to recognize that buildings are an optimization problem. We need to optimize the energy we consume, the resources we consume, with occupant comfort and productivity. It's a changing problem. It's not static, and I think that’s the other thing that has come out of a pandemic — that we can't assume that buildings can be controlled from a static point of view. It needs to be dynamic, it needs to adapt.