The transformation of U.S. transportation to electric vehicles requires a massive deployment of fast chargers that is being slowed by a debate over whether utilities should own and operate charging facilities, analysts on both sides of the debate agree.

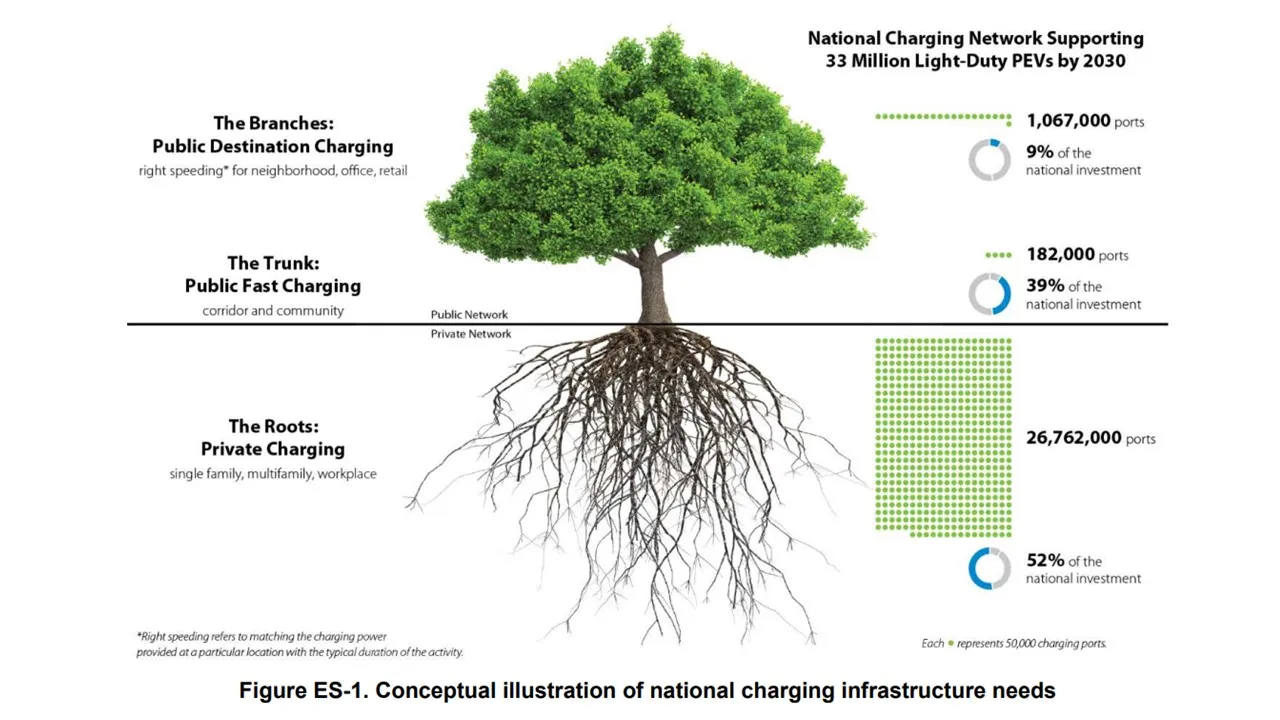

To grow today’s estimated 10% of new light duty zero emission vehicle sales to the national 2030 target of 50% will require a change “unprecedented in the history of the automotive industry,” a June 2023 National Renewable Energy Laboratory, or NREL, study reported. Utilities and charging companies widely agree with NREL on the huge need for public charging but not on the key providers to meet it.

Utility investment can accelerate the deployment of fast chargers, especially if regulators allow cost recovery for proactive infrastructure development based on planning, many stakeholders do agree.

But utility cost recovery for charger capital costs means the rates of non-EV owners, including lower income customers, would subsidize higher income EV owners, said Electric Advisors Consulting Founder Frank Lacey, co-author of a May 2023 paper opposing utility charger ownership. “Those subsidies inhibit private sector investment by giving utilities competitive advantages over other charging providers,” he said.

New policy, funding and goals to support transportation electrification have, however, “changed the rules” on utility spending, making costs to grow charging acceptable to many stakeholders, responded Alliance for Transportation Electrification, or ATE, Executive Director Phil Jones, co-author of a June 2023 paper advocating for a bigger role for utilities’ in charger deployment. Investments in utility distribution systems have become necessary and pivotal “market enablers” in this transition, he added.

Fast charger deployment must match charger usage to protect the financial viability of investments in charging infrastructure, which will require policy reforms, including proactive utility planning and procurement practices, many stakeholders said. But whether utility ownership and operation of chargers is necessary to meet the coming need remains in dispute, advocates for and against utility ownership agreed.

Costs covered, debates growing

The cumulative cost for the 182,000 publicly accessible direct current fast charger, or DCFC, ports to support the forecast of 33 million EVs in 2030 will be $27 billion to $44 billion, NREL estimated.

Capital commitments from private investors, governments and utilities in the U.S. are over $20 billion, a May 2023 Atlas Public Policy report found. And the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act and 2021’s bipartisan infrastructure law offer “significant” further support.

But continuing policy battles, like the question of the utility role, “are not doing much good for customers, reliability, or affordability,” said Cisco DeVries, CEO of distributed energy resources aggregator OhmConnect.

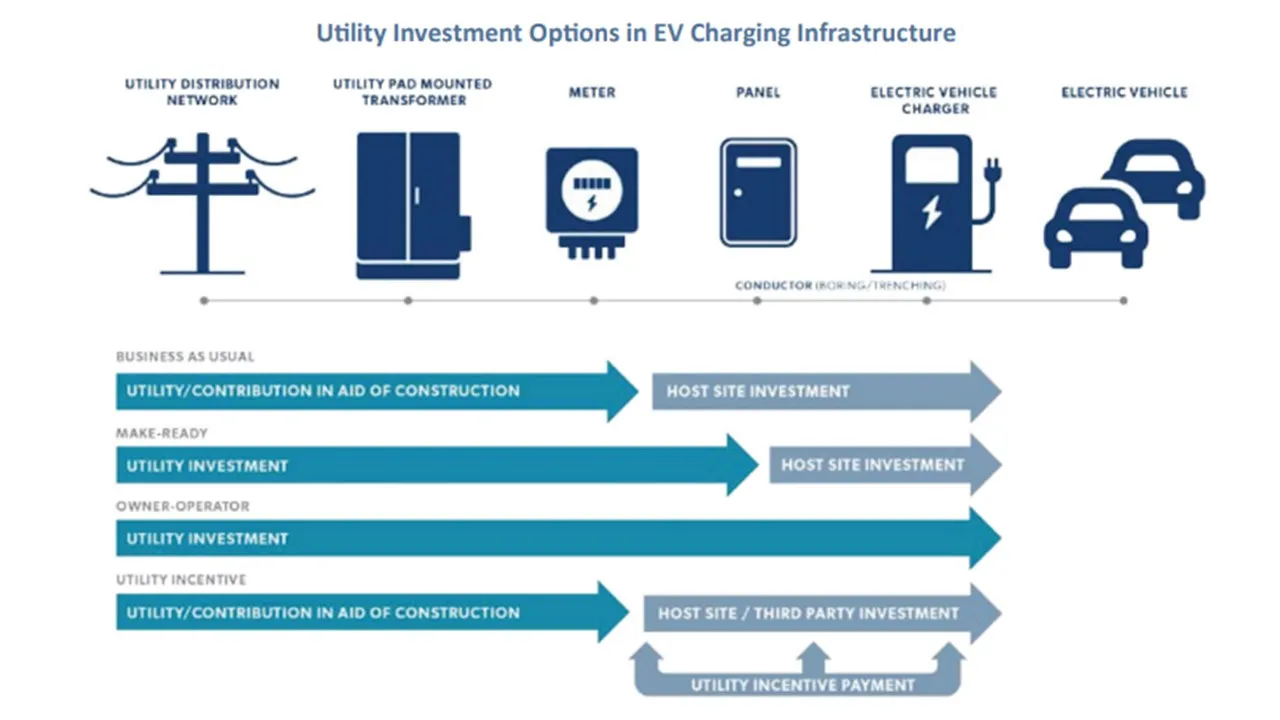

Some recent state policy developments have enabled utility ownership of charging facilities, but more often [they] have limited utilities to owning infrastructure up to the charger, or to ownership only for underserved customers, North Carolina Clean Energy Technology Center Associate Director, Policy and Markets, Autumn Proudlove reported from the Center’s Q1 2023 EV policy update.

Similarly, legislators and regulators have followed legitimate arguments for limiting and for not limiting utility charging facility ownership.

A private market?

“Customers need conveniently deployed and readily available public DCFC stations,” said Lacey, whose May 2023 paper was funded by the National Association of Convenience Stores. But competitive advantages from leveraging recovery of chargers’ capital costs through rates could allow utilities to build charging facilities at easier to develop but less highly trafficked locations convenient for drivers, he said.

Convenience store owners want to invest in charging stations, Lacey said. But competing with “subsidized utilities” could inhibit investment and slow the urgently needed scaling of public charging, he added.

Limiting the utility role in charging facility ownership protects utility customers from the “costs for charger O&M that can be done better by charger providers,” Lacey said.

Utilities could, however, support charger providers by designing new EV charging rates that limit the impacts of demand charges, “while charger utilization is too low to significantly threaten demand peaks,” he added.

Demand charge reform is needed, agreed Justin Wilson, senior director, utility partnerships and regulatory affairs, for charging station hardware and software provider ChargePoint.

Identifying and implementing new demand charges has already created common ground for utilities and charger providers. Utah’s Rocky Mountain Power, or RMP, and Arizona Public Service, or APS, whose regulators approved them owning public charging, are implementing new demand charge rate designs, both utilities said.

But EV charging “should ultimately be done by the private competitive market” in a future with the majority of parking spaces offering fast charging, ChargePoint’s Wilson objected.

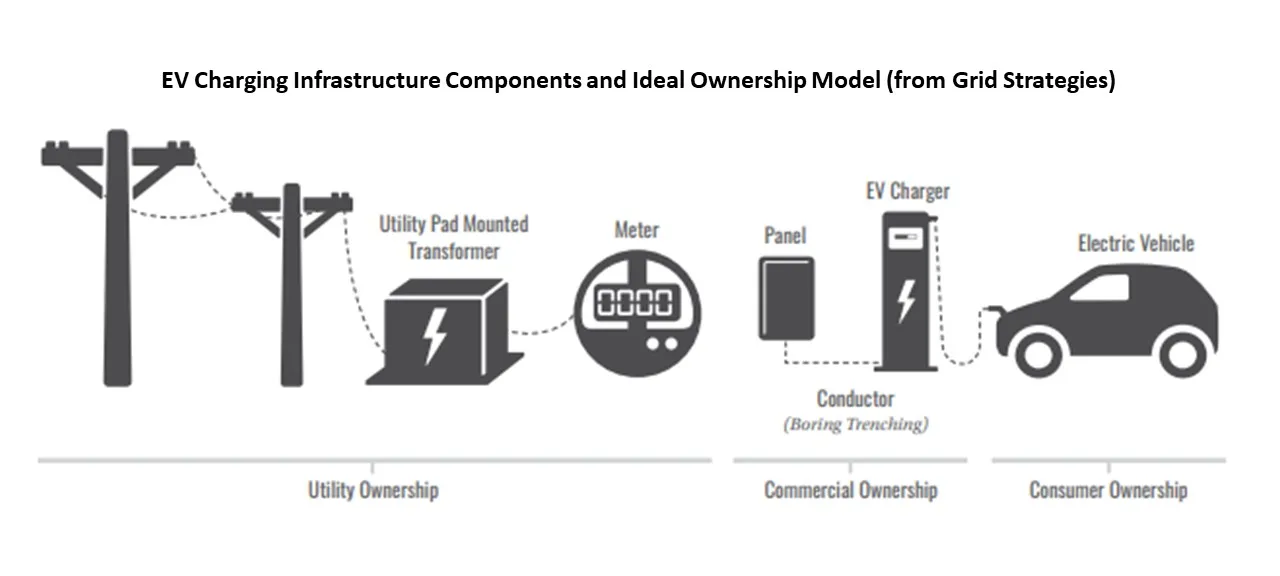

“The utility’s best role is doing interconnections as quickly as possible and deploying distribution system infrastructure up to the make-ready,” Wilson added. A make-ready is the utility-built hardware needed to interconnect a charger.

“The private market excels at deploying capital to expedite charging station installation,” Wilson added. But interconnections are a significant roadblock tying up capital and regulators should require utilities to expedite infrastructure upgrades and streamline interconnection for technologies like EV chargers that are prioritized by policymakers, he added.

In addition, regulators can accelerate electrification by approving utility cost recovery for proactive procurement of system infrastructure to meet anticipated utility planning needs, Wilson said.

As the debate over ownership of EV charging stations continues, utilities are not waiting to act.

Utilities in control

Despite opposition from some charger providers, utilities like RMP and APS are moving into charger ownership in partnership with one of the U.S.’s biggest private charger providers, which some stakeholders see as potential common ground.

An earlier program allowed public charging site owners to choose the charger and O&M provider but RMP studies found “a pattern of poor maintenance by private providers leading to bad consumer charging experiences,” said RMP Director of Innovation and Sustainability Policy James Campbell. Utah’s new RMP-backed H.B.107 allows the utility to own, obtain cost recovery, operate and oversee O&M for DCFCs, he said.

Electrify America subsidiary Electrify Commercial was chosen to deploy the RMP-owned and labeled DCFCs because of its next generation technologies and proven ability to meet high O&M standards, Campbell added. APS also chose Electrify Commercial to bring a smaller but similar public DCFC program online in January for similar reasons, said APS Energy Innovation Program Consultant Tony Perez.

Putting the utility’s brand on chargers makes it imperative for it to protect system reliability, Campbell said. Non-utility charging facility owners focus primarily on ways “to maximize profit,” but system planning allows utilities the visibility to deploy efficiently and manage charging loads “for the system’s benefit,” he added.

Electrify America’s ownership and operation of over 850 DCFC stations with about 4,000 ports on highways and at urban, suburban and rural commercial sites produced a key insight, said Senior Manager, Commercial Networks and Fleets, Aaron Young. The realization that “utilities want to own charging but need expertise or scale to do it cost-effectively led to Electrify Commercial,” he said.

It is vital to eliminate utility concerns about O&M service, reliability, and the customer experience because “there is still nowhere near enough U.S. investment” in DCFC deployment, Young said. Electrify America can take care of that on behalf of utilities, and other charger providers are exploring the opportunity, he added.

“California’s Public Utilities Commission ruling to proactively build EV charging infrastructure could make sense in other states.” said Young.

There are other reasons utility ownership can benefit EV charging facility deployment, advocates for utilities said.

A “unique” feature of utility investment is “patient capital” that can be invested with a longer-term view, said Edison Electric Institute Director, Electric Transportation, Kellen Schefter. It can fill “gaps” where third parties see no value proposition, he added.

And utilities are “accountable under formal regulatory oversight,” Schefter said. Their “track record” of meeting regulatory standards for identifying and addressing reliability challenges is “a skillset that will carry over to EV charging infrastructure,” he added.

Despite their differences, utilities and charger providers are successfully collaborating in states where regulation requires it.

Better together?

As the need for fast charging deployment becomes more evident, many utilities and private charger builders are finding that working together is the way to meet the challenge.

Like RMP and APS but without direct utility control, Ford and “leading charging providers” are developing its BlueOval Charge Network, a "network of networks" that includes about 1,800 DCFCs, said Ford Director, Electric Vehicle and BlueOval City Communications, Emma Bergg.

Austin Energy, a municipal utility, recognized in 2011 that “having chargers without vehicles is annoying, but having vehicles without chargers is far worse,” said Austin Energy’s Strategist for Electric Vehicles & Emerging Technologies Cameron Freberg.

“Public charging is becoming an expected amenity,” Freberg said. But “the best dollars spent by the utility are on the make-readies because they are long-term assets,” which is why Austin Energy has shifted its early charging ownership strategy to building make-readies for private charger providers who commit to its “station host agreement,” and allow monitoring of O&M performance to ensure reliable charging, he added.

Utility customers who drive EVs are shifting from an “if you build it they will come” attitude to a we “will go where the charging is available” attitude, Freberg continued. They will be dissatisfied with utilities that don’t support charger deployment in whatever form serves them best, he added.

That demand by drivers for more and better charging is why “all utility options to deploy charging facilities, including building make-readies and owning and operating chargers with or without a charger provider partner should be decided by state regulators,” added ATE’s Jones, a former Washington state utilities commissioner.

Utility grid modernization capital expenditures for grid modernization or building make-readies may be the best approach in regulated utility markets if private charger provider investment is adequate, Jones acknowledged. Most utilities want investments in distribution system situational awareness to safely integrate rising levels of EV fast charging but may “prefer to avoid the time and cost for charger O&M,” he added.

Southern California Edison, or SCE, is an example of that approach. It “primarily builds make-readies rather than competing with charger owner-operators, said SCE Director of Electrification Chanel Parson. But it still takes steps to protect the customer experience, she added.

SCE’s practices show how stakeholders with different business models are moving toward the same target of reliable charging. To plug into SCE make-readies, charger owners contractually agree to keep every port operational for 10 years and to provide monthly reports detailing operations data for each port, Parson added.

Those are practices described by RMP’s Campbell, in a utility-owned program, and by ChargePoint’s Wilson, as a best practice for a charger company.

Like SCE, National Grid New York is focused on “bringing power through make-readies to the chargers” because it does not want to compete “where the private sector has animated the market,” said National Grid Director for Transport Electrification, New York, Brian Wilkie.

But a key National Grid concern is obtaining wider regulatory approval for proactive procurement and development of system infrastructure that utility planning and forecasting studies show will be needed as charging loads grow, Wilkie said.

A longstanding lack of investment means distribution systems require modernization, agreed Ken Munson, CEO and president of distribution system software provider Rhythmos. “But as the EV adoption curve ramps up, it is outstripping utilities’ ability to upgrade assets,” he said.

Private charger providers like ChargePoint also agree. Utilities cannot meet policy mandate timelines for EV growth “if they have to do [distribution system] upgrades at 10 MW of new load and again at 20 MW or new load,” he added.

A best approach to accelerated charging facility deployment may require one more factor, some stakeholders said.

The time factor

Despite emerging agreement on the need for demand charge relief, interconnection reform, and new approaches to utility cost recovery, the debate on the utility role in EV charging facility deployment is missing something, stakeholders said.

“Utility distribution systems are now the pathway to value from new technologies like EV charging and utilities now should have the ability to choose how to optimize that value while protecting reliability,” ATE’s Jones said.

But if policymakers do not prevent utilities from leveraging their competitive advantages, charging will be too “economically inefficient” to attract investment and EV adoption will be impeded, Lacey said.

The charger market “is still taking shape” and stakeholders are still “learning the optimal approach,” said Rhythmos’s Munson. Over time, “utilities have built the environment that exists” and solutions going forward from both utilities and private providers “will be extensions of that existing value,” he added.

Correction: This story has been updated to clarify that Electrify Commercial is not working with regulators or any other parties to allow utilities to build and recover costs for EV charging infrastructure.